Sean Garwood is genuinely nostalgic for his years as a deepsea fisherman—a career that started in 1978 and spanned a total of 27 vessels. He is happy he went to sea and worked with absolutely wonderful people and there is not a day goes by he doesn’t think about fishing.

The love for the sea, in both a fishing and art context, started young.

Garwood grew up in Fremantle, Western Australia, and accompanied his dad at work on pilot boats and tugs from the age of five.

“It was a boy’s dream,” he says.

Garwood’s father was also a painter, who held sell-out exhibitions across Australia.

“He was a very accomplished marine artist, with commissions from major shipping companies and even has one of his paintings hanging in the Australian War Museum.”

Garwood drew inspiration from his father, who was soon able to give up the sea and paint full time.

Coming up 16, school took a backseat to working on an Italian cray boat, drawing ships in Fremantle harbour, and sailing.

Prior to the Garwood family moving to New Zealand in 1979, three trawlers arrived from Holland as deck cargo on a heavy lift vessel: the Tangawai, Ikiwai and the Galatea.

Garwood was enthralled watching the ‘super trawlers’ being unloaded and fortuitously met the vessels’s skippers: Brian Hardcastle, Johnny Gay, and Brian Kenton—who encouraged the lad to stay in touch.

“I subsequently worked with all three of them!”

Motivated to pursue a career at sea, he wrote a letter to Peter Talley, receiving a courteous handwritten offer of assistance.

His maritime career was launched with Skeggs in Nelson aboard the Waihola but many vessels followed: Waipori, Seafire, Otago Challenge, and the Otago Galliard.

What followed was a nomadic sea life, fishing from Timaru to the Gulf of Carpentaria; from exploring for orange roughy is South Africa to catching orange roughy on the Challenger Plateau. Garwood finally settled down in Nelson with Sealord on the Aoraki and the Rehua and finally the new-build Aorere.

All this time, Garwood was drawing and turning handdrawn charts into artwork.

“I used beautiful fine draughtsman’s paper and very fine pens. All the depths were recorded and finally the contour lines. The charts became 3D in a way.

“I must have been a bloody nerd because most of the crew were down the pub and I would be at home finishing the charts. “

In 2004, he discussed with his wife Ligliana the idea of becoming a full-time artist.

“It was a huge gamble considering we had two young daughters, but we backed ourselves and got on with it.”

Garwood started off with painting still life subjects, nostalgia, and country sport.

“This taught me valuable lessons with the classic medium of oils. Painting is a process which evolves over many years,” he says.

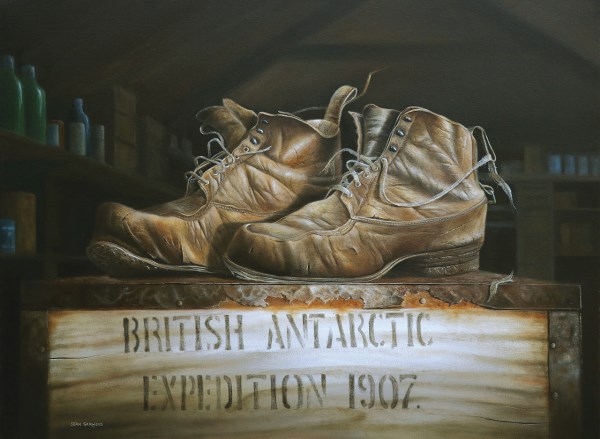

In 2015 Garwood submitted a proposal to Antarctica New Zealand to visit, sketch and photograph the historic huts of Shackleton and Scott, with the aim to stage an exhibition in 2017.

Garwood says the Antarctica trip was life changing.

“I was alone in Shackleton’s hut—it was three o’clock in the morning, and broad daylight—a moment to reflect. “These humble wooden buildings are a treasure trove of early Antarctic exploration. Symbolic of the arduous journeys of the Shackleton and Scott expeditions. They are also the birthplace of Antarctic science. It was a privilege and a very humbling experience.

“They call it ‘the white silence’. It is so quiet it is deafening almost. The wind came and was funnelling down the kitchen range chimney, it was quite haunting but very spiritual. You could feel the presence of Shackleton and his men. It was so powerful because inside the hut the artifacts are so well-preserved due to the air being so dry. For example, there is still jam on a piece of bread that is 110 years old but looks like you could pick it up and eat it.”

He gained enough material to spend two years in his studio painting his Antarctic series and a subsequent exhibition in Christchurch. New Zealand Post later featured the paintings on postage stamps.

Then his agent suggested he change his focus to marine painting.

So, in 2017 he started preparing for a 2020 exhibition—the most comprehensive visual survey of New Zealand’s rich and diverse maritime history ever assembled by a solo exhibition.

“The research involved has been extraordinary. I have met such generous people who have loaned me rare books, shared their memories and advised me on technical issues for some vessels. If it wasn’t for them and the inspiration they gave me to paint each vessel, it would have been very difficult,” he says.

Garwood is disappointed in the lack of recognition given to mariners in New Zealand.

“For a country so dependent on shipping from colonisation to trade, there is very little in way of raising the public awareness of our maritime success.”

I asked Garwood about his techniques for painting the ocean, as marine painting is considered the most difficult genre to master.

He explained that a lot of successful maritime artists in the 1800s and 1900s ‘served before the mast’. They had a knowledge of rigging and could paint by instinct.

“You have to be technically correct when painting a ship, but not so technical that you lose the poetry of the painting. One of the most important aspects is the connection between the vessel and the water.”

There is a saying that you must know the ocean to paint the ocean.

“To experience the ferocious great Southern Ocean in all her glory will always remain in my memory. One could never properly interpret these scenes from books or photographs. You must feel the ocean beneath your feet and watch how a vessel reacts to her ever-changing moods. When you have that experience, the interaction between the vessel and the ocean comes out in the painting naturally,” Garwood says.

Garwood says it is not surprising that classic marine paintings are becoming extremely rare.

“There are a number of reasons, including the time involved in creating these works. Ship’s rigging can be extremely complex, especially square-rigged sailing ships. It requires careful planning and draftsmanship, that few have the required patience, knowledge, and ultimately the dedication for,” says Garwood.

“My days of going to sea may have passed. However, I am extremely grateful that I now have the opportunity to craft paintings that reflect my time at sea and document our rich and diverse maritime history. I feel that my painting career is paying back now to a part of my life that I was extremely fortunate to have and never took for granted,” Garwood says.

Sean Garwood’s work can be seen here: Sean Garwood or at seangarwood. co.nz