Pāua is one of New Zealand’s most iconic and popular fisheries. Most are familiar with the regulations around pāua harvesting – bag limits ranging from 2 to 10 per person per day (depending on location), and the minimum legal size of 125mm around the whole country (with regional exceptions of 85mm in Taranaki, and recently 135mm in the Oaro-Haumuri Taiāpure south of Kaikoura).

Minimum legal size (MLS) is one of the most widely implemented fisheries management tools. It ensures that animals can reach maturity, and then remain for enough spawning seasons to enable sufficient reproduction to sustain populations. The underlying rationale for setting the size limit for pāua at 125mm is uncertain, although studies from the 1980s indicate that this was deemed appropriate based on yield-per-recruit modelling to sustain fisheries at the time (based on data from the Kaikōura and Banks Peninsula area) (Sainsbury, 1982). The rule of thumb for setting MLS in abalone fisheries is often described as the “2-year rule”; that abalone should be allowed to reach maturity, and then grow for two years during which they can contribute to spawning (although recent best practise now leans towards 3-4 years). This means that the size at which pāua reach maturity, and annual growth increments after this are two critical biological parameters to be considered with the setting of MLS.

However, it is well documented that pāua exhibit geographic variability in both length at maturity and growth rates around New Zealand. With specific regard to growth, pāua from warmer northern waters tend to grow slower than pāua from cooler southern waters, although growth is also influenced by other factors such as food availability, wave exposure and other habitat related factors. This means that the ‘one size fits all’ size limit of 125mm for pāua across most of New Zealand is inappropriate, as it is likely too big in some northern areas, and too small in the faster growing areas of the south to adequately protect spawning biomass and sustain populations.

Most will be aware of the exception to the 125mm MLS in the Taranaki Region where the MLS was lowered to 85mm in 2013 and there has been a recent increase to 135mm in the OaroHaumuri Taiāpure area of the Kaikōura coastline to reflect the biological characteristics of these populations.

However, large parts of the fishery are still able to be harvested at an MLS which is most likely inappropriate for specific regions.

In the commercial fishery, the variation in biological characteristics of pāua populations at different scales is recognised in the implementation of variable minimum harvest sizes (MHS) across most of the fishery. Up to 5 different MHS are implemented in some of the pāua QMAs up to as large as 145mm on the East Coast of Marlborough.

The primary benefit of increased harvest size is that is leaves pāua in the water for long enough to reproduce to sustain populations by protecting a larger proportion of the spawning biomass before it is susceptible to harvest. Another equally important benefit is that protection of a larger proportion of the spawning biomass allows for higher potential for the creation of ‘spawning aggregations’ which are critical for successful recruitment. Pāua are broadcast spawners, meaning males and females release sperm and eggs into the water column synchronously, after which fertilisation, and larval development and dispersal occurs before juvenile settlement. For successful fertilisation, it is critical that mature males and females are in close enough proximity, which is enhanced by protecting a larger proportion of the spawning biomass with larger MLS.

Despite the well documented evidence for the appropriateness of multiple MLS around New Zealand to responsibly manage our pāua fisheries, as well as the intuitively obvious sustainability benefits, there are several arguments against changes to MLS in paua fisheries that are often raised.

One of the most common arguments is that increasing the MLS will then increase the fishing pressure on larger pāua which have the largest reproductive potential. It is true that in pāua, like many other fisheries species, that fecundity (measured by the number of eggs produced by a mature female) increases significantly with the size of the animal. There is evidence from studies undertaken in the 1970s that shows pāua egg production increases exponentially with shell length, with the possibility that this may decrease after a certain size of about 150mm (Poore, 1973). However, another important consideration for reproductive success is also the egg quality, which may deteriorate in older and larger pāua. While there is no scientific evidence to show this, we know anecdotally from experts who spawn pāua for aquaculture purposes, that pāua in the size range of 125-135mm have the highest spawning success rates.

This suggests that pāua in these size ranges possibly have the highest reproductive potential and make the most meaningful contributions to recruitment.

If this is the case, it further supports the argument that increasing MLS in some populations will have significant positive benefits for population sustainability. Also, as mentioned earlier, proximity of spawning adults (‘spawning aggregations’) is also critical for reproductive potential, and can be significantly enhanced by increasing MLS. This is a specific area that we are currently interested in researching further to make decisions with greater scientific certainty.

Even in the case where the largest pāua do have the highest reproductive potential, increasing MLS will not have a material effect on the numbers of large pāua harvested. Compare this to the snapper fishery, where the release of large snapper is encouraged due to their high fecundity as well as the ecological role that large snapper play in their ecosystems – pāua are not a catch and release fishery, and harvesting large pāua is not avoided under the same conservation principles. To the contrary, divers will usually target the largest pāua they can find and even high-grade catches to maximise the feed they can take home.

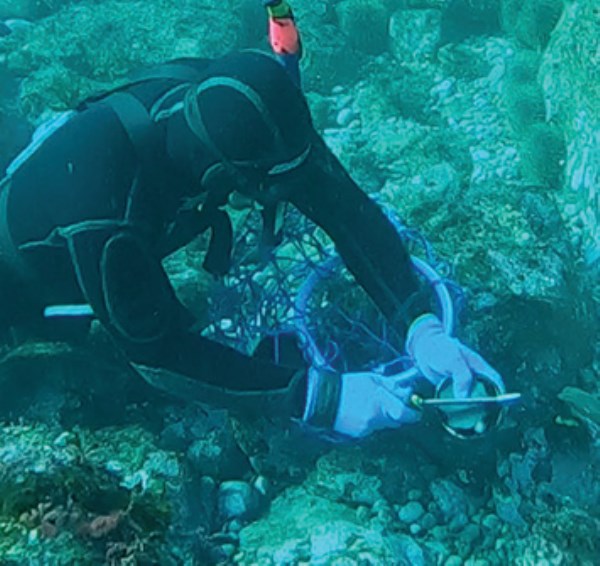

Another commonly raised argument against increasing MLS is that it will increase the rate of incidental mortality as harvesters have to adjust to catching pāua at larger sizes. Incidental mortality is a valid concern with pāua, as returning undersized pāua can result in mortality if they are injured during harvesting. However, it does not take much to ‘get your eye in’ as you are harvesting to be sure that you are only removing pāua over the relevant MLS, after which the rate of incidental mortality becomes constant no matter what the MLS is. The key messaging here is to ensure that harvesters use the right tools and techniques during harvesting to reduce the rate of injury to undersized pāua, specifically: using blunt tools such as the Fisheries New Zealand pāua tool, approaching pāua from the back to dislodge them (away from the pointy end where the head and vital organs are concentrated), and to leave pāua alone once they are disturbed and strongly fix themselves to the bottom.

Variable MLS also require the need for different measuring tools to be used and an awareness of regional regulations and can introduce a layer of complexity for enforcement in some specific cases. While this can be an adjustment, there are multiple species around New Zealand where different sizes limits exist in different regions (e.g., Snapper) where the inconvenience of needing multiple measures and enforcement difficulties are not an issue.

Another benefit for the diver harvesting pāua at a larger MLS is the yield of meat that comes from pāua harvested. The meat weight of a 125mm pāua is 125g and from a (for example) 135mm pāua is 160g, which is almost a 30% increase in what ends up on the table, regardless of how many you take.

Despite the adjustments that have to be made for all when MLS changes, any inconveniences and arguments against are far outweighed by the overall sustainability benefits that arise from protecting a larger proportion of the spawning biomass, allowing longer for pāua to spawn, and significantly enhancing the opportunity for mature pāua to form spawning aggregations. Forward thinking and regional based management that recognises the different biological characteristics of this iconic species in different regions is essential to its long-term sustainability.